On Inventing

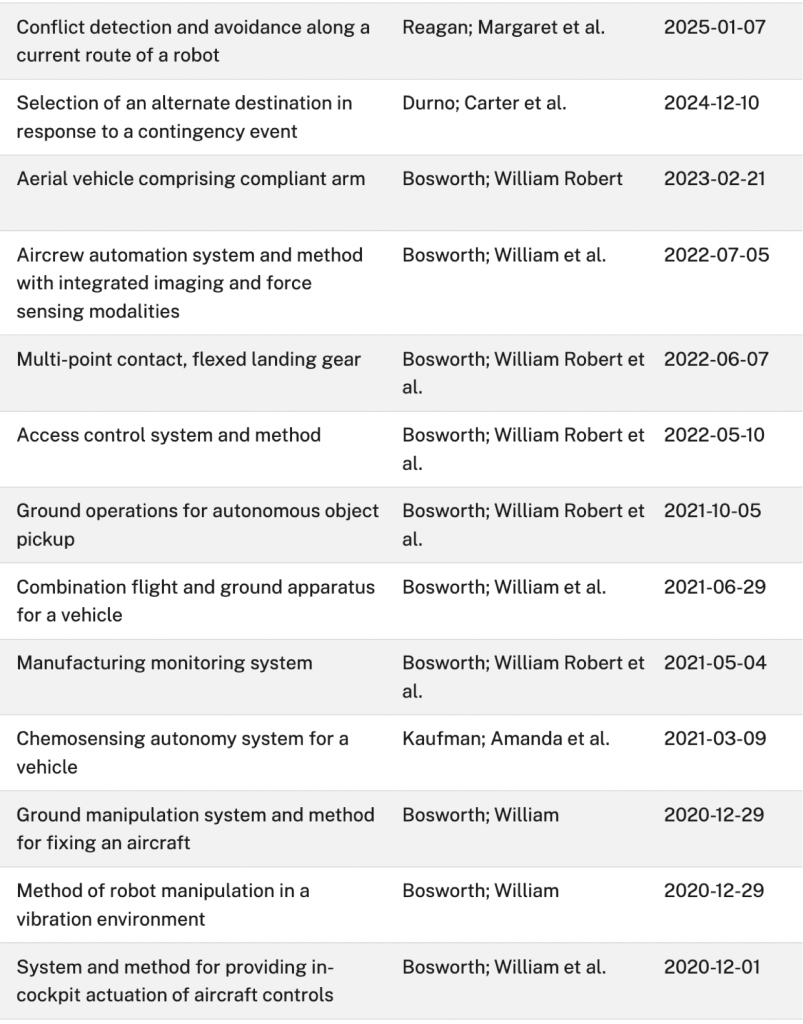

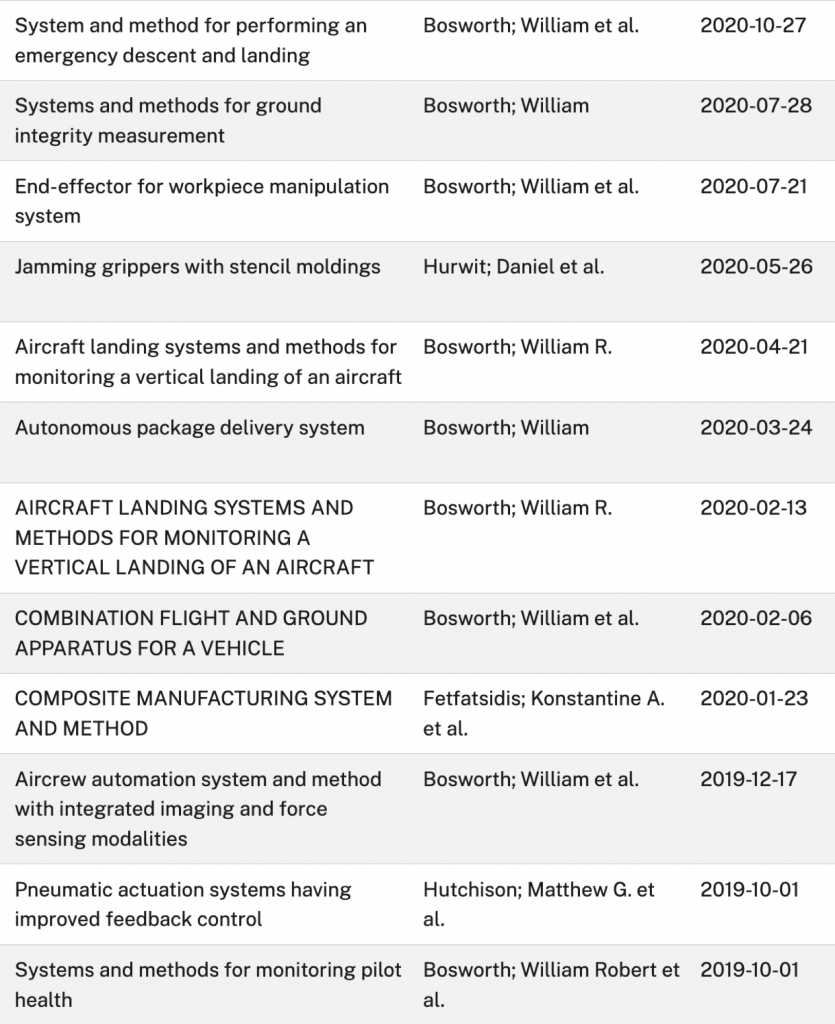

Inventing new things is a gratifying part of my career; a list of some of my inventions, as USPTO granted patents, are pasted below. At work I get a lot of questions about how I patent so much. The short answer is 1.) I learned how to write in grad school, and I am more diligent than most people about actually writing down my inventions and submitting them to the patent lawyer; 2.) I intentionally carve out time to be open to inventing: I create a purposeful habit and put in the time; 3.) I try not to be too perfect and I try to be kind to myself when my “new” idea for the week ends up being a dud. Being knowledgeable about my field(s) is helpful to avoid reinventing the wheel, though if I invent something that already exists, I try to use it as positive feedback that my idea had merit.

A few books have influenced my approach on the topic:

FUNdaMENTALs of Design is a textbook that Professor Slocum used when he taught 2.007, the Mechanical Engineering design course. I had the good fortune of taking 2.007 with Alex, and also performing undergraduate research with him; he also oversaw parts of my master’s thesis work.

If you’re not prepared for it, it can be exhausting and intimidating to work with someone who is so full of ideas. But, if properly harnessed it is super inspiring and fun. One grad student in Prof Slocum’s lab once told me, “Alex has an interesting idea every hour, and my job is to figure out which ones are the really good ones.” I think Alex’s book does a great job of describing how to be open to new ideas while also being disciplined about when and how to act on those ideas.

Songwriter’s on songwriting interviews 50+ famous and successful songwriters. Some writers start with words; others start with melodies. Some do it in their heads; some write it down; others record snippets. Some write at 10am every morning, put in their 2 or 3 good hours and stop; others wait until late in the night and binge. One thing is for sure: all of them write a lot of songs. Even “one hit wonders”–those who only get known for writing one song–write a huge amount content.

Thomas Edison is famously quoted, “If you want to have a good idea, have alot of them.” The same is true for any creative endeavor: if you want to write a good song, write alot of them. If you want to invent, invent.

This video of The Police is a neat look into their songwriting process. In 1981, The Police were hugely successful giants, but they still faced the same struggles and process needs as any other creative person.

Bird by Bird is a charming text on famous author Anne Lamott’s approach to writing. I read it over and over again because it makes me feel courageous. I’ve adopted the index card habit from the book: I keep boxes and boxes of “ideas” and other plans, and when I’ve got spare time I open the box and see what I might push on next.